- Home

- Joni Tevis

The World Is on Fire Page 3

The World Is on Fire Read online

Page 3

Click. In an upstairs bedroom, a soldier tucks a mannequin woman into a narrow bed, the mattress’s navy ticking visible beneath the white sheet. Outside the open window, the white blare of the desert at noon. Downstairs, another soldier arranges a family, seating adults around a table and positioning children on the floor, checking the dog tags around each of their necks.

What’s a plan but a story, set not in the past but the future? Someone in the Civil Defense Administration already decided how many mannequins this house will hold, what they’ll wear, whether they’ll sit or stand. But surely this soldier can allow himself the freedom to choose, say, which game the children on the floor will play. For Brother and Little Sister, how about jacks? A good indoor game. And Big Sister, let’s set her off from the rest, next to her portable record player, its cord lying on the floor like a limp snake. Father leans toward the television, one hand on his knee and the other on the pipe resting in the hole drilled in his lip. The blank television reflects his face; he could be watching the news.

The tremendous monetary and other outlays involved (in testing far away) have at times been publicly justified by stressing radiological hazards. I submit that this pattern has already become too firmly fixed in the public mind and its continuation can contribute to an unhealthy, dangerous, and unjustified fear of atomic detonations. . . . It is high time to lay the ghost of an all-pervading lethal radioactive cloud (to rest). . . . While there may be short-term public relations difficulties caused by testing atomic bombs within the continental limits, these are more than offset by the fundamental gain from increased realism in the attitude of the public.

—Rear Admiral William S. “Deak” Parsons, 1948

In 1945, Manhattan Project physicists exploded the first atomic device, Trinity, in the desert outside Alamogordo; a little more than two weeks later, the Enola Gay dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima, and three days after that, Bockscar dropped Fat Man on Nagasaki. Scientists predicted that the United States’ monopoly on atomic weapons would hold for at least twenty years, but in 1949, the Soviets proved them wrong, exploding a bomb named First Lightning. In response, Harry Truman authorized the building of Mike, the first hydrogen bomb, tested in the South Pacific. The logistics of testing so far away made the process costly, so a public relations campaign was conducted in order to convince Americans that testing closer to home—at the Nevada Test Site, an hour or so north of Las Vegas—was desirable and safe. By and large, the public got on board with this campaign, and although much of the evidence generated by the tests was kept classified for decades, the Department of Defense and the Atomic Energy Commission made it a priority to publicize some of the information. Broadcasts of the tests were shown on television, newspaper reporters and photographers documented them, and civilians were encouraged to witness the explosions.

In the summer of 1957, an article in the New York Times explained how to plan one’s summer vacation around the “non-ancient but none the less honorable pastime of atom-bomb watching.” Reporter Gladwin Hill wrote that “for the first time, the Atomic Energy Commission’s Nevada test program will extend through the summer tourist season, into November. It will be the most extensive test series ever held, with upward of fifteen detonations. And for the first time, the A.E.C. has released a partial schedule, so that tourists interested in seeing a nuclear explosion can adjust itineraries accordingly.”

Hill’s article suggests routes, vantage points, and film speeds, so that the atomic tourist can capture the spectacle. But is there anything to fear from watching an atomic explosion? Rest assured, he says, that “there is virtually no danger from radioactive fall-out.” A car crash is the bigger threat, possibly caused by the bomb’s blinding flash or by “the excitement of the moment, [when] people get careless in their driving.”

In the article’s last paragraph, Hill writes, “A perennial question from people who do not like pre-dawn expeditions is whether the explosions can be seen from Las Vegas, sixty-five miles away. The answer is that sometimes enough of a flash is visible to permit a person to say he has ‘seen an atomic bomb.’ But it is not the same as viewing one from relatively close range, which generally is a breath-taking experience.”

That summer, after winning the title of Miss Atomic Bomb, a local woman poses for photos with a cauliflower-shaped cloud basted to the front of her bathing suit. Thanks to trick photography, she seems to tower over the salt flats on endless legs, power lines brushing her ankles. With her arms held high above her head, the very shape of her body echoes the mushroom cloud, and her smile looks even wider because of the dark lipstick outlining her mouth, a ragged circle like a blast radius. Not only do Americans want to see the bomb, we want to become it, shaping our bodies to fit its form.

A studious-looking young man who totes his electric guitar like a sawn-off shot-gun.

—Review of a Buddy Holly performance in Birmingham, England; March 11, 1958

There’s a lot going on during that atomic summer. Buddy Holly, for instance. His career’s taken off by 1957, thanks to hits like “That’ll Be the Day,” “Peggy Sue,” and “Everyday,” songs that combine country inflections with rock’s insistent rhythm. He looks ordinary, like someone you went to high school with; in fact, you were born knowing him, the bird-chested guy, sexless and safe. But look more closely: at the story of how he gets into a “scuffle” with his buddy Joe B., the bass player, before a show, and Joe B. accidentally knocks off Buddy’s two front caps. Buddy solves the problem by smearing a wad of chewing gum across the space, sticking the caps back on, and playing the gig. Or at the story of how he met dark-haired Maria Elena in a music publishing office and that same day asked her to marry him—and she said yes. Or look at this, a clip from a TV show he played in December of ’57.

“Now if you haven’t heard of these young men,” the hostess says, “then you must be the wrong age, because they’re rock and roll specialists.” The camera’s trained on Buddy, and he doesn’t waste time: If you knew Peggy Sue, then you’d know why I feel blue, giving it everything he’s got, and as he moves into the second verse, the camera on stage right goes live, and he pivots smoothly, keeping up. I’m staring back from better than fifty years out, watching as he follows the camera with a studied intensity magnified by the frenetic speed of his strumming. His fingers are a blur, but he doesn’t make mistakes, and as I watch the clip, I’m startled by the distinctly handsy look in his eye. This is not what I expected.

The whole song’s a revelation, from the rapid-fire drumming, to the stuttering Pretty pretty pretty pretty Peggy Sue, to the way his falsetto warps the words of the last verse. With a love so rare and true—you know he doesn’t mean a word of it. He’s just telling you what you want to hear, and that tamped-down sex—how had I missed it?—burns in his eyes. And there’s something about the way he stares at the camera that sets him apart from his contemporaries. Elvis, the Big Bopper, Johnny Cash all play to the audiences they have at the time, mugging for the camera and making the kids squeal. Jerry Allison, the drummer for the Crickets, said later that playing on TV made him nervous: “That was something different,” he said, “an audience that wasn’t there.” But watching Buddy, you’d never know it. He’s playing to the fans of the future—to the camera, to now.

First floor, living room. First floor, dining room.

Children at play, unaware of approaching disaster.

—“Declassified US Nuclear Test Film #33”

(Apple-2/“Cue”), 1955

Ever since I watched La Bamba as a kid, I’ve known about the plane crash that killed Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. “Big Bopper” Richardson. It happened before my time; it was a foregone conclusion, verifiably historical. Knowing that, I couldn’t see Buddy Holly as anything other than a dead man walking, doomed to die young, tragic. But of course there’s more to him than that.

He was a writer, for one thing. The year before that TV appearance, he’d gone to the movies with his friends and seen a John Wayne picture. T

hat’ll be the day, Wayne kept saying. Well, that was a nice line, and he wrote it down, to see if he could put it to use.

Not long ago, I watched The Searchers myself, trying to figure out what about that line had compelled Buddy Holly. The movie follows Ethan Edwards, played by John Wayne, over the course of five years spent tracking a band of Comanche across the desert Southwest. He’s trying to find his niece Debbie, kidnapped as a child during a raid on her family’s ranch. Along the way, other riders join Ethan, but you wouldn’t call them his partners. He’s the one calling the shots, and he’s vengeful, cruel, and all the more dangerous because he has enough cultural know-how to really hurt his enemy. This image stays with me: when the group finds a Comanche warrior buried under a stone, Ethan opens the grave and shoots out the corpse’s eyes. “Now he’ll have to wander forever between the Spirit Lands,” he says, leaving the twice-blinded body behind.

For me, the movie’s most compelling moments are the early ones leading up to the raid on the ranch. In a low-ceilinged adobe room, Debbie’s mother scolds her older daughter for lighting a lamp and revealing their presence. “Let’s just enjoy the dusk,” she shrills, trying to hide how frightened she is. Outside the half-timbered window, the desert glows white-orange, sunlight pouring in like fear made visible. Her voice cracking, she orders Debbie to run away to the family’s burial plot and hide there: “Don’t come back,” she says, “no matter what you hear.”

That light, brilliant and threatening, stays with me. No matter what Mother tries to pretend, this is no ordinary sunset. We don’t see the war party attacking the ranch; it’s enough to see the helpless family anticipating disaster, and the aftermath, in which nobody’s left standing. When Ethan and the rest of the men return to the ranch, they find it a smoking ruin, the death inside so grisly they can only allude to it. “Don’t let him look in there,” Ethan commands one of the men. “It won’t do him any good to see it.” The people killed had been Ethan’s brother and his family, but he doesn’t show signs of sorrow or surprise when he finds them. You can’t catch him off guard. He’s an icon, not a real man, and he says “That’ll be the day” four times.

ALERT TODAY

ALIVE TOMORROW.

—Poster, Mr. Civil Defense, 1956

Seems like nothing goes according to plan. The date for Apple-2 had been set well in advance, but after weather conditions force several delays, some of the would-be watchers pack up and head home; surely some of them regret missing the chance to see the bomb up close. Finally, conditions are right, and the countdown begins. Just past 5:00 a.m., full dark over the desert, photographers brace on boulders overlooking Frenchman Flat, and soldiers hunch in trenches. The speakers crackle, and the announcement goes out for observers to put on their dark goggles; those without goggles must face away from the blast. A transmitter broadcasts canned music that pours from the radios in the houses of Doom Town. It plays in the dark rooms as of a house asleep, but only one resident is in her bed. In the dim living room still smelling of sawdust and damp cement, Sister reclines on the floor beside her record player, and Father leans toward the dark television, pipe clamped in his mouth.

Not far away, a reporter embedded with a group of soldiers takes notes from inside a fifty-ton Patton tank. “‘Sugar [shot] minus fifteen minutes,’” he writes. “Then it was ‘sugar minus ten’ and ‘sugar minus five.’ Someone tossed me a helmet and I huddled on the floor.”

We just hoped somebody would buy our records so we could go on the road and play.

—Niki Sullivan, rhythm guitarist for The Crickets

Sometimes it must seem he’s never known anything but life on this bus, its engine groaning up the grade of every back road in the Upper Midwest, his clothes wrinkled and ripe in the bags overhead, his hands tucked under his armpits for warmth. When the bus breaks down again and the heater conks out, they burn newspapers in the gritty aisle between the seats to try and stay warm. Carl, the drummer, gets frostbite and has to go to the hospital. He’s a fill-in; Joe B. and Jerry are back in Lubbock. But Buddy needs the money. On cloudy days after snow falls, you can’t tell where the fields end and the sky begins, and the fences down the section lines must be a comfort to him. Iowa’s a long way from Texas, but at least the barbed wire tells you what’s solid and what’s not.

They all play the show in Clear Lake and gear up for Moorhead, nearly four hundred miles away, a full night’s ride in that freezing bus, and probably another breakdown on the side of the road. Why not charter a plane instead? Then he’ll get to the next gig in plenty of time, have a hot shower, do everyone’s laundry. The Beechcraft seats three plus the pilot. He’s in for sure, and J.P., sick with a cold. Ritchie and the guitar player flip for the last seat, and Ritchie wins. See you when we see you.

And I’m not married yet and I haven’t got sense enough to realize the magnitude. You see it visually but it’s beautiful. It’s beautiful. Just gorgeous, the colors that are emitted out of this ball of mass, and the higher it goes into the air, it becomes an ice cap on top of it because it’s getting so high, and it’s just a beautiful ice cap.

—Robert Martin Campbell Jr., describing test George, the thermonuclear detonation he witnessed in the Marshall Islands on May 9, 1951

The plane’s thin door clicks shut. Past midnight, and Buddy’s beat. The pilot turns the knobs and checks the instruments, and the engine roars its deafening burr. When he looks out the windshield, there’s nothing to see but snow, swirling in the lit cone thrown by the hangar lights. Slowly at first, then faster, the plane rolls down the runway and lifts off. Up, and bouncing in the air pockets, the roar of the engines, no way to talk and be heard but he’s too tired to talk anyway. Three miles out, then four, then five.

When do they realize something’s wrong? Does the pilot panic, trying to read the dials and not understanding what they say? The windshield’s a scrum of snow, white-swirled black, no way to tell up from down and headed for the ground at 170 miles an hour, the plane shaking hard, going fast, and this gyroscope measures direction in exactly the opposite way from the instruments the pilot had known before. What does it feel like? You can’t trust your senses when you’re this beat, this far from home, and all you know for sure is that your bones hurt from hunching into the cold. One day you’re playing the opening of a car dealership outside town; the next you’re leaving the movies with your friends; the next you’re on The Arthur Murray Party, standing in front of a girl in a strapless ball gown the color of winter wheat. She’ll stand there the whole time, swaying gently, looking over your shoulder at America and wearing a little smile that says there is nothing better than this, to be here in this place, young, feeling this song in your body, warm inside the theater while outside the wind blows, louder and louder, sneaking its way in through any crack it can find and shrieking now in your ear, higher and colder and harder and harder until finally it stops.

Amen! There’s no more time for prayin’! Amen!

—The Searchers, 1956

The second hand on the watch’s round face ticks toward vertical: three, two, one. A great flash, then peals of thunder, and a wall of sand radiates out from ground zero. When the heat hits the house, its paint smokes but doesn’t have time to catch fire. The shock wave rolls over it, the roof lifts off, and the whole thing collapses. Two and one-third seconds since detonation.

There’s a lot of atomic film out there; you can watch the bomb explode as many times as you can stand. But although the different cameras and jump cuts can make the clips hard to follow, the View-Master parcels out a single image at a time. Push the reel home with a click, and put the eyepieces to your face. All of the images on this second reel are colored yellow, everything lit not by the sun, but by the bomb. A bomb with a twenty-nine-kiloton yield, about twice as powerful as the one dropped on Hiroshima. “Observers are silhouetted by the Atomic Flash,” reads this caption. I stare at the dark shapes of the people, the bleachers, and the telephone poles behind them, everything outlined in a gleaming

yellow that could almost be mistaken for a very bright sunrise, but the color’s all wrong. Like many other shots, Apple-2 was detonated before dawn specifically so that the photographs taken of it would be better. And I have to admit, this is an image I can’t forget.

Next slide. Here’s our house, the one with Father and Big Sister in the living room. As “the heat burns the surface of a two story house,” smoke issues from the roof and from the car in the driveway, a ’48 Plymouth. The house’s front windows, blank and white, reflect the fireball. Click. By the next image, when “the shockwave slams into the two story house,” the window glass is gone, the roof canting back as the siding dissolves in granular smoke. Support beams fly up as the trunk shears from the Plymouth, and already the light has changed to a pallid yellow, the black sky less absolute, greasy with smoke and sand, carpet, copper wire.

Click. On this house, a one-story rambler, the roof goes first. Smoke rises from the gravel drive, the portico, the power lines. “The house is blown to pieces from the shockwave,” says the caption; I click back to the previous slide and can’t find anything I recognize. Click. When “an aluminum shed is crushed by the shockwave,” the roof and sides crumple inward in a swirl of dust. Click. The last slide shows a stand of fir trees, brought in from the Siskiyou Forest in Oregon, maybe, or the Willamette. Soldiers implanted them in a strip of concrete, a fake forest built of real trees. There’s a rim of low mountains in the background; in the middle distance, this strange forest, bending in an unnatural wind; and in the foreground, no seedlings or fallen logs, just the flat expanse of desert, covered over by what might be choppy water, or snow. And if any stowaways were hiding in the trees, bagworms in the needles or termite colonies under the bark, they’re vaporized like everything else, flat gone.

Live a bucolic life in the country, far from a potential target of atomic blasts. For destruction is everywhere. Houses destroyed, mannequins, representing humans, torn apart, and lacerated by flying glass.

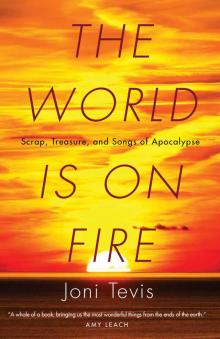

The World Is on Fire

The World Is on Fire