- Home

- Joni Tevis

The World Is on Fire Page 2

The World Is on Fire Read online

Page 2

A telling detail hides in the house’s thirteenth bathroom: a spiderweb window Sarah designed. The artisan rendered the web’s arcs in balanced curving sections of glass, but this is shorthand; in any real web, something more pleasing than symmetry develops. After all, symmetry leaves gaps, and if prey escapes, the spider starves.

Jean-Henri Fabre, a French naturalist writing during Sarah’s lifetime, noted that the orb-weaver spider works in a method that might seem, to the untrained observer, “like mad disorder.” After the initial triangle, spokes, and spiral, she rips out the preliminary threads, whose remnants appear as specks on the finished web. (In one added room of the Winchester House, you can make out the slope of a previous roof, a vestige of what the house used to be.) The spider fills out the web, testing its tension as she goes, finally building up the “sheeted hub,” a pad near the web’s middle where she rests and waits. Fabre calls this area “the post of interminable waiting.” When night fades, the spider destroys the web, eating the silk as she goes. Says Fabre: “The work finishes with the swallowing.”

The spider carries within her belly a store of this strong, pearly stuff, which nobody has yet been able to replicate. She dashes along an invisible line to bind a fly with bights of silk; she bluffs her foes by “whirling” or “shuttling” her web at them. Naturalists used to carry scraps of velvet to the field, so they could have a better backdrop for examining the webs they found. An entrepreneur once made wee cork-padded cuffs and fitted them to a spider’s legs, then wound skein after skein of silk from her spinnerets until the creature ran dry. He repeated the process with thousands of spiders until he had enough material to weave a gray gown of spider silk, which he then presented to Queen Victoria. During World War II, British gun manufacturers used black widow silk to make crosshairs for rifle sights.

As for me, when spring comes, I keep a lookout for the “sea of gossamer,” as it’s been called, when spiderlings take flight. In summer I have spied many a tight purse or reticule in which a swaddled grasshopper still struggles, staining the silk with dark bubbles of tobacco juice. And in fall I watch big garden spiders move from holly bush to camellia, spooling out guy lines and waiting under the streetlight for miller moths. With articulate legs, they pluck strands of silk and load them with gum. When dawn comes they finish hunting and tear down their webs, swallowing the golems a line at a time.

The Winchester House was once a living thing, Sarah’s shadow self, breathing in and swelling out, tough as twice-used nails. There are many threads to this story; many entrances, but only one safe exit. Not the door that opens onto a one-story drop, or the one that opens onto slats above the yellow kitchen. Sarah knew the way out; she designed it. After she died, movers needed maps of the house to empty it.

The house’s largest cabinet is the size of a generous apartment. A cabinet is a container, a room with single-minded purpose. Pliny tells of a house built of salt blocks mortared with water; how the sun shining through those walls must have glowed red at sunset. A fitting shelter for ghosts: crimson, translucent, walled with tears.

Sarah knew her house to be founded on blood, invocations written on the walls, looping script of glue holding the heavy wallpaper tight. Such a house, built for the dead, turns itself inside out, night after night. Windows mutter curses, drains align with Saturn rising, nails turn from gold to lead. She moved veiled through her nights, knowing what others did not, and placing a coin on every tongue her guns had stopped. Some jaws opened easily, others she wrenched apart, still others (blown away) she could not find: for these she placed gold on the breastbone, flat as a plectrum. The hum of voices grew. Sarah heard them all.

Step through a little door. “Welcome to the séance room,” the guide says, and something about the room does feel mysterious. Not just because of the thirteen hooks in the closet, or the three entrances and one exit (two doors only open one way). Here was where Sarah moved the flat planchette across the divining board, spelling out messages from the dead. The room feels like a sheeted hub, a knot.

Samson spoke false when he said, Weave my hair into the web of your loom, and I will become weak as any man, but it would have been natural for Delilah to believe him; superstitions about weaving have been around as long as knots themselves. Part a bride’s hair with the bloodied point of a spear. Forbid pregnant women from spinning, lest the roots of the growing child tangle. To treat infections of the groin, tie the afflicted person’s hair to the warp of a loom, and speak a widow’s name (Sarah, Sarah, Sarah) with every knot.

Move from legend to artifact and find hair jewelry, a practice that reached its obsessive height during the Victorian era, a way to keep a scrap of an absent loved one close. Women wove locks of hair into watch chains, button covers, and forest scenes, or braided ribbons from forty sections of hair, weighting them with bobbins to pull them flat as they worked. In Boston, a man had two hundred rings inset with locks of his hair and had them distributed at his funeral; their inscriptions read “PREPARE TO FOLLOW ME.”

When Sarah searched for the center of her life she found her child, quick breath in her ear, warm weight on her heart. She remembered the slight rise and fall, remembered counting the breaths, standing in the dark nursery past midnight, holding her own breath to better mark her infant’s.

She tucked a simple lock of baby’s hair in a safe and knitted a house around it. Whose grief could be more lavish than hers? She wove a row of rooms—hummed calls toward the dead, boxes made of music, measure upon measure. Began, like a spider, with three: herself, her husband, their child. Or herself, the rifles, those slain. The séance room has three entrances, but only one exit. The Fates hold three lengths of line and a keen edge to cut them.

From three points, she moved outside of language, opening the priceless front door, stepping over the threshold and bolting the door behind her. Spoke notes and rhythm and commerce (per box of dried apricots, less the cost to grow them). In her youth, she had spoken four tongues, but now she spoke the language of nails, to which no one could reply. While her carpenters built, she spoke through them, though they remembered nothing beyond Worked on the kitchen today. They cracked jokes about ghosts while they worked, but that wasn’t what made them uneasy; it was the way she used them to get outside speech. A good enough reason for paying them double—once for building, twice for hiding her secrets. Her army of men, working day and night, could drive a nail for every bullet sown and not feel the debt of guilt she had to bear. No wonder she kept them working throughout the dark hours.

In a gravel-floored aviary, Sarah kept tropical birds. To understand the speech of sparrows, touch a marigold to your bare foot on the appointed day. Tuck a bittern’s claw into your lapel for luck. The blood of a pelican can restore murdered children to life.

I read Aesop’s little-known fable, “The Lark Burying Her Father.” The lark lived before the beginning of the world. Water stretched out before her; she hollowed a home in the mist. When her father died, she was forced to let him lie unburied six days, because there was no earth to cover him. Finally she split open her head and buried her father inside. To this day, her head is crested like a burial mound.

Spared the problems of the birds who would come after her—the myrtle tree to ensnare, the gems to distract from food—the lark’s difficulty was elemental. Just the primary problem of grief, and not a bit of dust to hand to help. Later, Aesop relates, she would tell her children, “Self-help is the best help.”

The problem of what to do with the dead was one Sarah also confronted. She buried her bodies in the usual way, then moved across the country and built a living house in which she buried herself, again and again. Pliny records that magpies, if fed on acorns, can be taught to speak. Going further, he claims that they develop favorite words, “which they not only learn but are fond of and ponder carefully. . . . They do not conceal their obsession.” Did any of Sarah’s tropical birds possess the power of speech? If so, what did she long to hear them say? Help or home or Mama, a name n

o one had ever called her? We don’t know if they were toucans or macaws or quetzals, whether they screamed or croaked, only that they were tropical and that they came, like Sarah, from far away.

After a quick pass through the basement with its ancient furnace and rust-stained cement floor, the tour ends and we’re escorted out a low door. Our guide takes her leave, and we’re free to wander the grounds, crunching along gravel paths between the carefully clipped boxwoods, the thirteen palm trees, and the bronze sculpture of Chief Little Fawn. Press a button by the fountain and listen to the talking box tell its story. A boy of twenty, probably a guide-in-training, studies a stapled script underneath an ancient grapefruit tree. It’s a lot to remember.

You can see anything you want in Sarah Winchester. Craft a story from what bits and scraps you know. Her house is the primary document left to show us who she was, and it’s so easy to read it wrong. What was she trying to say? Was the house a letter to herself, or a cryptic message to the outside world?

Whatever the place is, it makes people uneasy. I heard it in the nervous banter of the other visitors. (“I think we should visit the firearms museum,” a man said to his son. “I think that would be interesting.”) (“She might have been too educated,” a woman said to our guide, who ignored her.) I can’t say whether the house is haunted or not, but it got under my skin.

Her naked display of long-term grief makes me flinch. Could I do any better? Could any of us? When her husband and child died, she mourned them the rest of her life. All that buying and selling couldn’t distract her. She did not hope for heaven—what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses his soul?—but let the world pass through her fingers: imported stone, brass smelted in faraway furnaces. Cared for none of it except as material bulk, something to make the house more than what it had been. Ordered the gardener to put in a new bed of daisies and hawthorn; paged through a catalog offering English yew and monkey puzzle, catalpa and persimmon, whose bitter fruit she craved.

For me, the stories about Sarah are the worst of it. All the easy myths, free of real life’s half-measures; the tour guide’s flip answers, and the dismissive chorus: She must have been crazy. In fact, in Sarah’s constant rebuilding of the house—an occupation with roots in the daily and domestic, but which she was able to take to new lengths because of her tremendous wealth—she looks a lot like an artist at work. If she’d been like her father-in-law, perfecting one object and mass-producing it, we’d remember her for her innovation and engineering. If she’d been like most upper-class women of her time, creating House Beautiful around her and then living out her life there, we wouldn’t remember her at all.

But Sarah Winchester did a bit of both when she created her house. Because she didn’t leave explanatory documents behind, all we have is the coded message of the house itself. Linger over its crabbed lines, fish-scale shingles, and old-growth redwood painted over to look like birch, and you’ll see she was doing what an artist does—leaving her mark and seeing what happened; working through an idea via metal, wood, and space; expanding the notion of what life is all about.

After we left the Winchester House, we stopped at an Army Navy store and bought a duffel bag to replace the battered coffee-pot box for the trip home—a step in the right direction. But long after I dragged the duffel through the door of our new place and started unpacking, I couldn’t let Sarah go. Dangerous, maybe, to take a big trip like that, when you’re between stages of your life, looking for work, unsure of who you are. I kept coming back to a postcard we bought in the Winchester House gift shop, a reproduction of the one extant photo of Sarah. She’s seated in a carriage behind a driver, and even though she’s at some distance, there’s a smile on her small, expressive face. She looks content, someone with work that needs doing. In that moment, she’s far away from the morning she buried her child, farther still from her husband’s rattling sickbed, and just like that she passes through the one safe exit into the realm where time shunts away and hours, days, thirty-eight years pass and she follows the unspooling line of her thought to its ragged end and looks up to see the marks she’s made. Floor, ceiling, wall; this covers me; this crowns me; this pushes me forward. Self-help is the best help: perhaps she believed it. But Sarah’s story ends not with a tidy moral but a dashed-off map. The movers, at least, would find that useful.

She could have filled scores of rooms with visitors. But in the end, the memory of her lost ones was enough for her. We are the crowd she never invited. (What are all these people doing in my house?) Now every day is filled with the tread of feet, the whisper of hands sliding along her banisters, the hum of conversations she can’t quite make out.

We signed a year’s lease on a brick cottage outside Apex. I spent my days running among libraries: an elegant domed one with a smooth marble floor, barrister’s tables, and an echo; the main one, eight stories and two sub-basements crammed with no-nonsense metal shelves; the zoology one, where I read Fabre in a cozy little carrel; the geology one, with maps of historic earthquake activity and potted succulents growing in deep-silled windows. I read an article about scientists feeding LSD to spiders to see how it affected their webs. I read that earthquakes leave coded messages in the earth around them, and that San Francisco politicians tried to deny the 1906 quake after it happened. That an old Roman myth tells of a gown made of moonbeams, and of the pages, with eyes sore and bloodshot, who carried it to Hera. That barbed wire used to be called “the devil’s rope,” and that you can tell the construction date of a house by the nails that bind it together.

At the time, it didn’t occur to me that I was obsessing over the details of someone else’s house even as I craved a place of my own. When our year’s lease was up, we moved to yet another state, where we’ve been ever since. Now we live in a tidy little bungalow with green shutters and a tight roof we paid for ourselves, with gleanings from those steady jobs we scoured the country to find. From this place of greater stability I see the Winchester House in another light: maybe an art installation, as I initially believed, or maybe just something to fill Sarah’s time.

Still, nights when I can’t sleep, I walk the halls of a darkened library, a place Sarah bequeathed to me. Her ramshackle house provided me plenty of work, paragraphs to draft and revise again and again, dry little suns to gnaw on, morsels sweet and tough by turns. Even now, telling these secrets, slick pages whisper beneath my fingertips and I smell marvelous old dust and glue. I breathe in air that carries with it words tucked between heavy covers, tales spelled out one letter at a time.

ACT ONE

Remove this sheet and keep it with you until you’ve memorized it.

SURVIVAL UNDER ATOMIC ATTACK,

OFFICE OF CIVIL DEFENSE, 1950

Damn Cold in February:

Buddy Holly, View-Master, and the A-Bomb

OK. So then when you get sent out to the test site, first of all I’m curious what your impressions of that were, because you are now in the middle of a desert compared to a—

It’s damn cold.

Yes, the desert’s cold in the winter.

In February, it’s damn cold.

First impression: cold.

And it’s dry, except when it rains.

—Robert Martin Campbell Jr.,

atomic veteran (Navy), describing his initial

impression of the Nevada Proving Grounds, 1952

Click through the images, one at a time. VIEW-MASTER ATOMIC TESTS IN 3-D: YOU ARE THERE! reads the package. The set’s reels show the preparations for the 1955 Apple-2 shot, its detonation, and the Nevada Test Site today. Three reels, seven images each.

Of the hundreds of atomic devices exploded at the Nevada Test Site from 1951 until 1992, the ones that stand out are those featuring Doom Town, a row of houses, businesses, and utility poles. It makes sense: the flash, the wall of dust, and the burning yuccas are impressive on their own, but without something familiar in the frame, the explosion can seem abstract. Doom Town—also called Survival City,

or Terror Town—makes the bomb anything but theoretical. These are the images I can’t forget.

Click. Here’s Doom Town’s iconic two-story house, a classic Colonial with shuttered windows balancing a front door. Neat and tidy, with white-painted siding and a sturdy red-brick chimney: if this were your house, you’d probably feel pretty good about yourself. But something’s wrong. The vehicle parked in the drive isn’t a Dodge or a Packard but an Army jeep; on the chimney’s edge, a bloom of spray paint shows the siding was painted in a hurry. This is a house nobody will ever live in. Its only inhabitants are mannequins with eyes like apple seeds.

All part of the plan, and the planning took far longer than the event itself. A crew unloaded telephone poles, jockeyed them upright, and drilled them into the alluvium. Down in Vegas, men bargained for cars and stood in line for sets of keys. Imagine the hitch and roar of a ’46 Ford, ’51 Hudson, ’48 Buick, and ’47 Olds as they pull onto the highway, headed for the proving grounds. Click. Here’s one of the cars now, a pale-blue ’49 Cadillac with 46 painted on its trunk in numbers two feet tall, marked like an entrant in a demolition derby.

You could say the whole country pitches in. Fenders pressed from Bethlehem steel, lumber skidded out of south Georgia piney woods, glass insulators molded in West Virginia, slacks loomed and pieced and serged in Carolina mills. And mannequins made in Long Island, crated and stacked and loaded onto railcars.

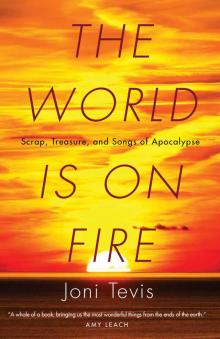

The World Is on Fire

The World Is on Fire