- Home

- Joni Tevis

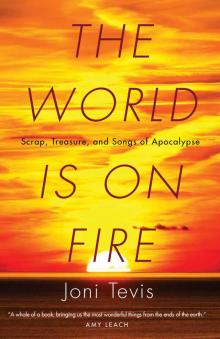

The World Is on Fire Page 8

The World Is on Fire Read online

Page 8

The idea was that we’d learn from it. Will a fresh coat of white paint reflect the bomb’s flash, protecting your house? What about a clean-swept yard? Is it safer to build walls of brick or cinder block? If you keep things tidy inside—end tables unburdened by magazines, sofa cushions tamped firmly in place—will your living room be less likely to catch fire? If you know what to do, you can save yourself. Your family too. And the unstated corollary: Do as we say, or you’ll have only yourself to blame. But what do we really learn? The house with the bare yard catches fire a few seconds later than the other, but still burns to the ground, sofa cushions and all. Said Val Peterson, Eisenhower’s civil defense chief: “The best way to be alive when an atomic bomb goes off in your neighborhood is not to be there.”

“I expected to see something like the fire that consumed the world,” atomic witness Patricia Jackson told a reporter. What had she hoped for—obliteration? She sounded disappointed to be spared.

Down in Vegas, the show went on. As one year melted into the next, Liberace’s trills and flourishes and between-song banter lengthened until they threatened to squeeze out the tunes themselves, and his gold lamé jacket grew into costumes ever more embroidered and embellished. Christmas, Stars and Stripes, King Neptune: what awed an audience last year bores them now. How can you top a two-hundred-pound outfit? The days of the $15 junk-store candelabra were a joke from the nostalgic past, reheated for his memoirs. Money wasn’t the limiting factor, creativity was. So: the double cape of pink-dyed turkey feathers, the ostrich ruff, the billowing ermine robe. Sooner or later, the joke wears thin. He must have felt it menacing him from around the corner. Which did he fear more—getting stale, or being found out? He never let an inch go to waste. So the folks in back could see it too.

As I watch old film clips of the atomic tests and Liberace’s shows, I start to think they’re cut somehow from the same cloth. The bright gleam of the desert at noon, what you shade your eyes against; the floodlit stage, what we still call the “theater of war.” I’m telling you the truth, and you won’t believe me.

Laughter from his last joke still hanging in the air, he ducks backstage for a costume change. An assistant hefts the cape onto Liberace’s body and the folds fall true, weighted with cabs and bugles, rhinestones and foil, satin rippled with embroidery and pimpled with seed beads. Heavy as a lead apron. He pushes back his shoulders, straightens his spine, and steps into the light.

What happened after the cameras stopped filming, and the journalists and the tourists packed up and drove away? The fallout drifted and spread and sifted silently to the ground, soaked into the soil and was absorbed by grasses, which were eaten by cows, whose milk children drank. When the children grew ill, their mothers wrapped their baby teeth in kraft paper and mailed them to scientists at Washington University, in St. Louis, who found that the teeth of the sick children held surprising amounts of cesium and strontium, which settle in the bones.

So in 1962, the bombs went underground, and over the next three decades, more than eight hundred bombs exploded beneath the Nevada desert. One of them stands out: Baneberry. Baneberry was a test that went wrong. On December 18, 1970, Baneberry was exploded about nine hundred feet underground; shortly after detonation, it broke through the desert, venting smoke and vapor and sand and dust ten thousand feet in the air. The radioactive cloud drifted high, far, wide. Just a matter of time, really: one tore through. Where do we go from here?

Fast-forward to a decade after Baneberry, smack in the middle of testing’s underground years. As the familiar strains of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto no. 1 play, a man rises theatrically from bed, dons a thick robe, and pretends to play along on a grand piano he has in his bedroom. As he walks through his house, performing his morning ritual—a dip in a swimming pool whose edges are tiled with piano keys; a mouthful of a piano-shaped chocolate cake—he continues to mock-play the concerto, grinning and tilting his head as if to say, It’s so nice to be in on this with you. Leaving the house, he drapes a floor-length ermine coat over his shoulders, steps onto a wide portico, and tucks himself into a rhinestone-encrusted Rolls-Royce. A handsome chauffeur closes the door with a click. Cut to an auditorium; timpani roll: “Ladies and Gentlemen.” “Proud to present.” “Famous for his piano” (brassy flourish!). “His candelabra” (!!). “MIST-er Showmanship” (!!!). “LIB . . . erace!”

The Rolls pulls up onstage, rhinestones winking in the glare, and the chauffeur opens the door to crashing applause. “Well, look me over,” Liberace says. “I didn’t dress like this to go unnoticed.” He’s a looker, all right, from his bouffant hair to his crystal-encrusted collar, a jabot of lace at his throat peeking out from under a bejeweled vest, hands brass-knuckled with amethysts and emeralds, sparkling oxfords on his feet. “Do you like it?” he asks. “You do? Wonderful, great. Sure,” he says, “there’s enough for all of you. Go ahead, help yourself. Oh yeah.” And the crowd eats it up. Stage right, the chauffeur tips his cap and eases the car offstage, tires squeaking on the polished floor.

Of course, it’s way too much. And yet there’s something about the glitter that feels exactly right. For me, glitz and apocalypse go together; I blame it on a childhood steeped in fire, brimstone, and Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. In the early 1980s, when Liberace’s show was at its most baroque, I watched his TV specials on Friday nights, and on Sunday mornings, I sat on the church’s left side so that I could see the pianist play. Her hair in a neat bob, her body obscured by a shapeless choir robe, she kept her eyes fixed on the music director as her small hands marched up and down the keyboard.

I knew I shouldn’t stare at her while she played. That made it too much like a show, and she performed for the glory of God. But why, then, did the choir stand onstage at the front of the sanctuary, even in front of the baptismal tank, where I had once floated buoyant in the water and afterward, sitting in the pew, pictured angels seated on the narrow ledges up by the ceiling? For that matter, why did we all applaud when the choir special was done? There had to be a little pride in that, a thing done well. God gives you the talent, but you don’t hide it under a bushel either.

My parents signed me up for lessons with the church pianist. “If you’re serious, you’ll keep your nails short,” she said. “Don’t let me hear them clicking when you play.” I did as she said, but noticed how Liberace performed with small stones bound to his fingers. (How do you play with all those rings on your fingers? “Very well, thank you.”) She taught me to read music and to practice every day, to count out loud to keep the timing straight, to respect the dynamics and tempo the composer had written. But from Liberace I learned that sometimes “too much of a good thing is wonderful.” And that people believe what they want to believe.

A diamond may be forever, but the rhinestones he wore were brazenly temporary, beautiful fakes. And the costumes required that he be sturdy. Never slight, never shy, or the suit wears you. He built his career on welcoming the audience into his life, yet there was this secret in plain sight, this lie they came together to create. Lee to his friends, Liberace on stage. You will not know me.

There’s something collusive about any performance: silently, the audience and the performer ask each other, Deceive me. Let’s make believe we’re friends, that the only exchange we’re making is of each other’s attention; don’t mention money. (But as Liberace said of his critics: “I cried all the way to the bank.”) Let’s pretend that this night isn’t like all the others; you know, there’s something special about you. When the spotlight focuses on the man in the glittering suit, little gleams multiply in the darkened auditorium. With a flash, the bomb detonates and the fireball expands. What would he play if nobody were listening? What would they detonate without a witness?

I have been too fascinated by bright surfaces, have stared too long at zinc nail heads blinding as sunspots. As a child of green shade, the desert out west has ever been a fantastic place for me, and I expected it to be paved with knobs of agate and slabs of quartz, not

dead antelope and wild horses and burned cattle. (Richard Misrach finds them in the vast expanse of the Nevada Test Site by following the crows who feed on the carcasses’ eyes.) Some official numbers: from 1952 through 1992, the year of the last official atomic test, 1,021 nuclear weapons were exploded at the Nevada Test Site. The first hundred or so were atmospheric, and the rest were underground, except for Baneberry, which was a little of both. A secret will always break through.

Since 1992, the Nevada Test Site’s Base Camp Mercury has become the region’s newest ghost town, something like the earlier incarnation of St. George, Utah, downwind of the tests and poisoned now for longer than anyone cares to say. Atomic detonations create radioactive fallout composed of (among other things) cesium 137, strontium 90, iodine 131, carbon 14, with half-lives of thirty, twenty-eight, five thousand six hundred years. Diamonds are forever, and these tests will always be with us. In Las Vegas, you can sign up for a bus tour of the Nevada Test Site. You can visit the abandoned control tower at Base Camp Mercury; you can see the only Doom Town house still standing, now a historical landmark, and eligible for federal preservation funds. You can see the crater that Sedan shot dug in the sand, the warped wooden bleachers where spectators sat, and shiny bits of metal and glass thrown out by the bombs, glittering now on that “dusty precursor-forming surface.” I’ve seen the day I would have visited the Test Site on a whim. Not anymore. Not for anything.

In 1987, not long after his fabulous specials featuring the sparkling Rolls and whipped-cream medleys, Liberace died of AIDS. It was a shock; the public hadn’t known he was sick, and even in his last interviews, he looks pretty good. Tanned, fit, a little thin, sure, but who wouldn’t look smaller, without those bulky show clothes? I grieved when he died, and so did everyone I knew. As for those rumors about his personal life, people said, Well, you can’t believe everything you hear.

You can’t take it with you. Not the mirrored piano or the world’s largest rhinestone; not the chunky jewelry or the gold-leaf ormolu desk that once belonged to Czar Nicholas II. But of all the things Liberace left behind, I love his clothes the best. One hot summer day not long ago, I visited the Liberace Museum in Las Vegas. I stood in the Costume Gallery a long time, staring at the mannequins and thinking of the man who had worn those gorgeous outfits and of the people who had labored to make them. Someone’s eyes burned under a bright task lamp as she knotted score after score of salt-grain beads to the pink-and-pearl King Neptune costume. Her palm took a bruise from the scissors handle, blade keening through inky satin; her foot pressed the sewing-machine pedal in her sleep. The finished product erased the chalk marks that preceded it, stray threads swept into the trash, misshapen beads cast aside, flourishes stretched longer and trills repeated until the ring fingers (always the weakest) gained strength like the rest.

It’s the furthest thing from a fallout shelter, this windowless room. No stolid cans of beans or Spam, no barrels of purified water. Just mannequin after mannequin dressed in sapphire or crimson, jet or rose, madder or lime, double-dyed, dusted with silver, crusted with cabochons. For the Stars and Stripes show, he wore a silk tailcoat in red and white, a platinum-beaded vest, and a pair of royal-blue shorts; in the Gallery, those clothes hung on a plastic figure over hairless thighs. On a shelf nearby sat a gift a fan had sent, a toy piano made of glued-together matchsticks. Any one of which could have burned the place to the ground.

It all gets back to the piano, doesn’t it? As an object, it demands space, a room free of drafts and direct sun, a sturdy foundation. In return it bears within its body the tension of tightened steel strings. Felt pads ritually pierced with a three-part needle. Its plate is bell-quality iron, dipped in shiny brass alloy for appearance’s sake.

I watch a factory film that shows how pianos are made. You start with lumber, hard rock maple; someone’s spray-painted a smiley face on the side of the lumber, but once it’s sawn into veneers, nobody will ever know it was there. A worker pours thin glue from a bucket. Another tightens a clamp around a form. Twenty-four hours later, they will remove the clamps and wheel the rim into a conditioning room stacked with empty pianos, their shoulders chalked with dates.

I keep noticing the workers’ hands. A woman tests the action by weighting each key with a lead cube. Her hands, small and strong and practiced, make notes with a gnawed pencil, its point whittled by a pocketknife. She is ensuring that the piano has the “proper depth of touch.” The man who installs the soundboard has knuckles whitened by fine sawdust. I can almost smell it as I watch him, as I watch another man plane the wood, as another man chisels a pattern on the rim with a keen blade. Table fans whir, and a locker is decorated with a newspaper photo of a man dunking a basketball and a bumper sticker that reads I LOVE MY UNION. The man who sets the pins and threads the strings (three for each note) wears fingerless gloves, his thumbs and index fingers taped for protection. “And now for the voicing,” says the narrator.

As an object, the piano draws you to itself. It sings and you resonate. A practiced hand plies a brush loaded with glue. Someone tightens a tuning peg with a socket. DON’T TOUCH, someone writes in red crayon on the piano’s fallboard. Its time has not yet come.

You can spend too long inside. I left the Liberace Museum, walked down the Strip to the Bellagio, and waited beside a wide, shallow pool whose turquoise floor was mined with hundreds of dark nozzles. People lined up along the wrought-iron railing, smelling of new T-shirts, their arms and necks beaded with sweat. The Bellagio gleamed white against an aquamarine sky; it hurt to look at it, hurt, too, to watch the duck paddling in the brilliant, chlorine-smelling water, washing desert dust from her wings.

At the stroke of noon, the jets clicked to life. DUM da da, three confident steps down to signal the beginning of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The water sprayed in time with the music in a carefully choreographed display, with some jets circling and others blasting water hundreds of feet into the air. As the nozzles twirled and the music blared, we gasped with pleasure.

After about ten minutes, the show’s finale started: “Con te partirò.” You didn’t have to understand the Italian, warped from the amplification system and the background traffic on the Strip, to know this song was the best kind of sad, show sad. The melody found and built on itself, knitted sixteenth notes climbing gently to a plateau. A breath. Then the chorus, Con te . . . partirò, slower now, simple and steady, a hesitant walk away, and with a backward glance the melody leapt high into a sob. It was a strange scene—the desert afternoon, hundreds of bystanders, a shimmering pool pouring forth music and light. And even though the show was completely manufactured, it still moved me.

I stood there thinking, Liberace would have loved this. Years before, his stage show had incorporated colored jets of water that arced and swirled to complement what he played—the exact precursor to this. And “Con te partirò” would have been just his kind of tune, sweeping and grand, a real tearjerker. The song satisfies our yearning to feel a version of sorrow in a group. We want to share this with other people, even if they’re strangers, even if it’s only for a moment.

Sure, Liberace seems like a phony. Sometimes I pity him—for the way he craved the audience’s applause, for how he tried to guess what they wanted, how he had to hide from them who he was. But as I watch the old clips, I see something more. After telling a joke for what must be the thousandth time about the enormous ermine coat he’s wearing, he strides across the stage, strikes a pose, and flings his arms wide as a prizefighter. In that moment, he’s triumphant; he’s not in his first or even his second youth, but he’s still the man of the hour, the one they’re all paying to see. And when he plays, I can’t take my eyes off him. Between the jokes, riffs, and “Chopsticks” played with two fingers, sometimes his grin fades, and in those moments, he’s not showboating. Just playing, and playing well. No, stores don’t stock Liberace albums anymore, but it doesn’t matter. The record, scored with its rings of iridescent sound, is as empty as the gorgeous robe without

a body animating it. There was something alive when he played, and he buried it as best he could, protecting it.

He was Liberace to his fans, Lee to his friends, and when the world first met him, he called himself Walter Busterkeys. It’s a Vegas litany—Busterkeys, Buster-Jangle, Tumbler-Snapper, Upshot-Knothole. Maybe the Bellagio stole Liberace’s “dancing waters” and raised them an order of magnitude, or maybe Liberace stole them from Baneberry—at ten thousand feet, that jet was still higher than any New High in the Las Vegas Sky. It’s all a show, and we participate in it every time we gather together and wait for something to happen. And at the end of “Con te partirò”—“Time to Say Goodbye”—the booming water cannons detonate with a sound undeniably martial, quoting Baneberry even if in a language we don’t realize we understand. When the explosion sets off the nearby car alarms, nobody notices. That ricochet of sound is just part of modern life. We take it in with the air we breathe; we hear it in our dreams.

Sometimes the performer and the audience want the same thing: to break the bonds of daily life by losing themselves in a shared experience. And sometimes they don’t want the same thing at all. The performer needs to be listened to, and the audience wants to be invited in. Let me see something different from the other shows. Make tonight special, even as I am special.

The World Is on Fire

The World Is on Fire