- Home

- Joni Tevis

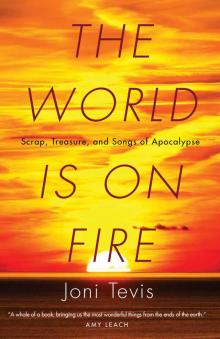

The World Is on Fire Page 13

The World Is on Fire Read online

Page 13

The salons have lighthearted names like A Cut Above, Hairsay, and Pat’s Palace of Beauty. We’re on the morning’s third shop by now. As the Scissorman chats with the manager, I watch a stylist work, thinking how she can walk miles without leaving the shop, pacing circles around the chair, pumping it higher with her foot, dropping a comb into the jar of blue Barbicide, slamming drawers closed with her hip, flicking hair from neck and shoulder with a soft-bristled brush. A full-body workout.

At her workstation, a jar holds a sheaf of brushes, cans of mousse line the counter, and a daughter’s school picture is taped to a mirror’s edge. Her scissors are by far her biggest work investment. Three hundred dollars a pair isn’t unusual. But it’s not just that. Her favorites must feel like an extension of her hand. They’re the claws we sometimes wish we had, sharp and efficient. They’ve cut her thumb clear to the bone before. Wicked. Their power is hers, and people give her a little extra for wielding it well.

It can’t be easy to make a living like this, always hunting work. People try to stretch things as long as they can, and in this economy, you can’t blame them. “Just don’t try to do it yourself, I tell them,” the Scissorman says. “That does more harm than good.” He makes his way one job at a time, carrying the years in his hands, in their healed scars and fingerless gloves.

He comes around like the change of season. Sometimes one long summer day passes exactly like the one before, and what’s to show for the time the stylist’s spent? Then he shows up, and she needs him bad because of her past twelve busy weeks—sixty shifts, five hundred heads of hair. Her work seems invisible, until he measures her labor by what he takes away. “Hair’s mostly carbon,” the Scissorman says, “and so are shears. In the beginning, the steel wins, but it’s a losing battle.”

At the day’s last stop, a converted bungalow in an older part of town, a stylist combs sections of an elderly woman’s fine hair onto rollers and pins them. The client’s rosy scalp shows through the neat rows of white curls, a tender place that nobody but her stylist sees. As we move through life, we’re held by strangers, dependent on their skill, on what they know about nape and temple, how they dance the line between job and generosity. Across town, a midwife bathes a newborn, a nurse wraps a joint with tape, and here, now, the stylist teases out the set to hide the thinness and sprays it to hold. The woman is “put together” now, elegant and respectable, ready for church or dinner with friends. You’d never suspect how little hair she actually has. The stylist leans back against the chair as her client makes her careful way out the door, into the bright afternoon. Like the Scissorman, she’ll be back.

We All Drink from that Fiery Spring

(Ode to Heavy Industry)

As the plane banks over Houston you will see the refineries of Texas City. If it is day, there will be a pillar of cloud over the smokestacks; if night, a pillar of flame. The plane’s engines drown out all sound but their own, but you will know the deep thrum the flares make. A sickish tint hangs over the city, sometimes whitish, sometimes yellow or brown, but remember: the fuel the refineries decant holds the plane aloft. I see in the refineries something I recognize. Dangerous, necessary. Here’s where we make things. Here’s where I’m from.

Dad’s factory sat between the railroad tracks and SC Highway 183. I worked there the summer before I moved to Houston, first shift, packing parts. The loading door stood open to let in the breeze. Kudzu crawled over the railroad siding. Check for chatter by running your fingertip across the barrel’s lip. Keep a red rag to wipe sweet kerosene from your hands. I could finish a box in twenty minutes, arranging spark-plug shells shoulder to shoulder, spraying each layer with a silver can to keep away rust, tucking one cardboard spacer between each layer. Five layers to a box. Sponge the kraft tape wet, pull it taut over the box’s seam and press it home, ink initials and date in the top right corner.

First shift started at 6:00 a.m. Barbara, my supervisor, kept a first-aid kit tucked under the counter, and a poster pinned to the wall that said, I’VE BEEN BEAT UP, KICKED, INSULTED, LIED TO, AND LAUGHED AT. THE ONLY REASON I STAY AROUND IS TO SEE WHAT HAPPENS NEXT. The secretary in the front office had air-conditioning, Gatorade, and access to the front restroom. We had to use the shop restroom; second shift smoked while they pissed and stubbed out the filters on the cinder-block walls.

I would move to Texas in August. I had never been there before, and for me—for everyone at the shop—it became a fabled land, a mirage that shimmered just out of sight in the heat waves that rose from the asphalt of the employee parking lot. One day during break, LaTrina, who ran the counterbore machine, said, “When you get out there on your own, whoo! You’ll be your own lady. Ain’t got no man to tell you what to do, ain’t got no kids to tie you down. I’d go in a minute.”

Friday was payday, and I’d deposit my check at the bank in town. Always there was someone in the teller line who’d turn around to see who smelled of old grease, sweat, hot metal. Always I’d look her in the eye and give her a tight smile. I don’t owe you a nickel, lady. A thousand miles to Houston meant forty gallons of gas, and I could pay for it. We all drink from that fiery spring, hear the refinery’s dull roar when the engine scrapes to life. Barbara said, “Once you get out there, you’ll never come back here. You won’t know us no more.”

Orders fell midway through the summer, and I got laid off. Cletis, the floor manager, said he was sorry to do it. Not long after that, Dad sold the factory out to a conglomerate from Connecticut, and they moved the machines from the shop beside the railroad tracks to a new white-painted building in town. Heavy-duty haulers moved the big green screw machines to the new factory and the workers bolted them to the floor. One of the machines, a chucker, had been stored in a cave in Kansas for decades. The federal government had had it built in 1947 to make parts for bomb detonators, tooled up and ready to go in case of another war. Engineers tested the machine at the factory in Connecticut, sprayed it with Cosmoline to keep it from rusting, wrapped it in heavy paper and burlap, and trucked it cross-country. Hundreds of these machines waited in the cave until 1993, when the government auctioned them off for a song. While similar machines would retail for better than a hundred thousand dollars, these sold for sixty-five hundred.

Strange to think of the old shop sitting empty now, the machines gone, Barbara’s first-aid kit and I’VE BEEN BEAT UP poster gone, the thumbtacks that held it to the wall gone. But curls of scrap must still be there, corkscrews of brass and steel pressed into the filth of the shop floor. And the smell of kerosene caught in the insulation. And the workbench I leaned against as I worked.

My old boss Cletis is gone, too, gone to glory. The last time I saw him, he was in intensive care in the hospital, recovering from a triple bypass. I would move to Houston a few days later. “Be careful out there in Texas,” he whispered. The tubes in his chest made it hard to talk. “Remember, when you marry one of them rich oil barons, I want to be the gardener in your mansion.” Bougainvillea, cycads, Chinese tallowtree. None of them plants that we knew. But I would learn them on my own, rich air pressing me down, the smell of roasting coffee from the Maxwell House factory swirling over my little garage apartment, and sometimes when the winds changed, the bitter fume of the refineries’ hot metal. I married not a rich oil baron but another writer, poor as me, and for years we have lived first carefully and now extravagantly together, today back not far from that railroad siding, where last night’s hard frost killed the kudzu back until next summer. Last time we visited Houston, I noticed a label on an air conditioner that read ALPHA AND OMEGA AC REPAIR. I am the first and the last.

Yesterday I asked if the old cave machine chucker was still around. “Kind of,” Dad said. “Made a new machine out of it. Took the original head out and scrapped it, put a new head in. Same frame.” Still running.

Hammer Price

(Song of the Auctioneer)

The auctioneer remembers. What it cost him to learn to chant ($37.50 for a class in 1978). The year this ho

use was built (1946; the deceased laid the bricks himself after returning from the War). What this bidder, a trim lady with carefully permed hair, will pay for a McCoy planter shaped like a bird-of-paradise ($80). “One more time, believe I would. Believe you’ll get it,” says the auctioneer as another man bids higher. “I was wrong,” the auctioneer says. “I have ninety, who’ll give a hundred, hundred, hundred? Nice piece,” he says. “Don’t shake your head. Don’t walk away.”

I like this auctioneer, and I go to all his sales. A big suntanned man with a neatly trimmed silver goatee, his chant is a pleasure to hear and easy to follow: playful, a bit of a twang, and a tobacco-auction echo in the soft-r way he sings “quarter.” By the sale’s very nature, we don’t want the same things, and yet he’s such a good salesman that I feel we’re on the same team. We need each other.

I love auction day’s carnival atmosphere. It’s an efficient treasure hunt; the place is flushed empty in a day’s time, and we each leave with what we wanted most. The auction saves waste by keeping goods in circulation. But for me, the best part is the chant, which rests on one note even as the auctioneer’s words dance and dip. On auction day, I rest inside the chant, and feel it bear my weight.

Most of these sales take place at old farmhouses along narrow roads; we park on the shoulder and unfold our chairs under shade trees planted years ago by somebody long gone. But today we’re in town, the Hotel Easley, a two-story brick affair with striped awnings, halfway between the high school and the funeral parlor. Like always, the auctioneer snaps on the PA at 10:00 a.m. and starts in. First item: a six-drawer dresser with attached mirror. He tries twenty-five dollars, “twenty-five, five, five.” No takers. So he drops to twenty, “twenty, twenty-dollar bid, all right, ten, am I bid ten, ten, ten. [Sigh.] Gimme five dollars, people, five dollars to start.” Someone hollers, “Two-fifty!” and six hands shoot up. It’s gonna be that kind of day.

When I grew up here in the 1980s, the Hotel Easley still drew textile managers visiting from out of town. But by the time I started high school, the hotel had turned into an old folks’ home—I remember a woman sitting on the deep front porch in the same chaise longue that waits in the dewy grass with a number zip-tied to its frame. When I moved away for college, the hotel was a halfway house for people who’d just gotten out of jail. And for years now it’s stood empty.

Its furnishings reflect that history. Dozens of dressers and nightstands, box lots of sherbet dishes, slippery old National Geographic magazines. But other items are harder to trace. Pillbox hats with traces of makeup staining their grosgrain insides. Pocketbooks, empty but for little mirrors in waxed-paper slipcovers that crumble under my fingertips. Slide rule, topo map, and a dissection kit nested in a case that snaps shut with a click. In a box lot, if you want one item, you have to buy the whole grab-bag bunch.

As the morning wears on and we shift to stay in the shade, I see bidders I recognize from other sales: the trio of white-haired sisters, the city dealers in the navy Jeep, that ponytailed guy whose shirt says, I COULD TRY TO CARE, BUT MY GIVE-A-DAMN BROKE. Auctions aren’t anonymous; when you register, you give the clerk your name, phone number, and a copy of your driver’s license. We must be a little ruthless to do this, haggling over possessions of the dead. But to buy at an auction is to start a new conversation with an old piece. I’ll remember this afternoon’s particulars long after I’ve forgotten a thousand other summer hours: the sudden downpour, pecan tree dropping pollen down my neck, boy pushing a toy bulldozer through the gravel.

“It’s like playing a banjo,” the auctioneer says, sitting across from me at a local diner where we’ve met to talk. “Start out, you can only play one note at a time. Then, over time, if you practice, you’re playing ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown.’”

I like him as much in person as I do on the block, where he sings, sometimes, for eight hours at a stretch. His hands are workingman’s hands, wedding band on one finger and a Mason’s signet on another, and the rise and fall of his pitch generates the power of the chant. “People get anxious when an item they’re interested in comes up,” he says. “You can sense it. Whether you say ‘hypnotize,’ or ‘get into the joy of the auction,’ the tune soothes people.”

At the sale last Saturday, I watched as his five-month-old grandson rode in the crook of his arm, staring at his granddaddy’s face while he chanted. Auctions are family affairs: his wife clerks, his son is a ringman, a daughter and a daughter-in-law calculate totals when buyers close out. But it’s more than that. “You’ll see families break up over stuff,” he says. Once a man had to buy back at auction a silver dollar his mother had promised him, years ago, and paid more than it was worth because his brother kept bidding against him. “When he won that thing, he held it up in front of everybody, said ‘I got my dollar back.’”

I love box lots for their quality of surprise. How does the auctioneer build them? “You got to put the good, the bad, and the ugly in there,” he says. “Something to catch that person’s eye. Think of a husband and wife. Think of a mother and a daughter.” That way, you run a better chance of getting multiple bidders involved. “All you got to do is spark a little interest. Old jacks they remember playing with, key chain with ‘Chevrolet’ on it. Anything to spark some memories back where it used to be.”

Oil lamp crammed with dead wasps, filling-station watering can, card table with two folding chairs repainted yellow. Canning jars starred with seed bubbles. Potluck casserole dish still labeled with her name. Hammer price does not include sales tax; all items sold as is, where is. Homemade toolbox, ’79 Ford, nightgowns. Child’s tea set, still in the box.

“Tew, tew, tew,” cries the mockingbird from the upper reaches of the pecan tree. “Five, five, anywhere five—HEP”, yells the ringman—“gimme ten, ten, ten.” The women in the front row murmur to each other, and out on the highway, a car slows down, then speeds off. Below all this is the sound of my heart beating, the house’s floorboards creaking beneath strange feet as people step into the attic and pull the chain on the bulb. Hiss of electricity, slap of the Porta-John door. The auctioneer keeps three things in mind: the have, the want, the next. The have is the current price, the want is what he’s asking, the next is a click past that. His guiding star is more.

What must we, the gallery, look like to him? Our faces worried or wanting, bored or at peace. As my eyes shift out of focus and I tuck my card under my thigh. As the woman next to me fidgets when the lawn mower comes on the block, and bids high. As that city dealer carries off an armful of hand-stitched quilts. The auctioneer mops his brow with a handkerchief and sips lukewarm water to open his throat. When learning to chant, try filler words such as Whatabout, bettaget, gottaget. Believe I would. “I like to drove my family crazy,” the auctioneer said of learning to chant. “On car trips, I’d sell telephone poles, cows, cars coming down the road. With repetition, you can do anything you want to do.”

Even when I forget that these objects once belonged to a living person, the auctioneer remembers, moving between the quick and the dead and striving to do right by both. “I want to do the best I can by the seller,” he told me, “but I want to protect the buyer too.” I remember a sale at a little house by the railroad tracks. She’d kept a garden. Even the rusty tomato cages were tagged and numbered but those purple irises bloomed for nobody but her.

When the sale day ended at the Hotel Easley, I paid for a set of jadeite mugs, a little cross painted with GOD BLESS OUR HOME, and what I wanted most, a bundle of old keys. One for each door at the Hotel, plus a master.

How many times did someone else do as I’m doing, rolling the key slowly between thumb and forefinger? People call it a skeleton key but really it’s a bit and barrel, and any lock it fits is easy to pick: bow, shank, bit. Now I can claim every room it opened. The tidy bed that waited for the widower, the pile of street clothes stiff with starch, the hook holding the bride’s traveling cloak. I can step over the threshold, knowing that once I do, someone here will look after me

. Mount the creaking staircase, set down my suitcase, and shut the door as the afternoon fades. Stare out the window as ripples of heat rise from the undertaker’s smokestack. And when night falls on a Friday you can hear the marching band play, Here we go, Easley, here we go; hear the crowd yell when a call goes their way. Later, after the late train runs, you’ll hear keys knock against each other as the hotelkeeper replaces one on its rightful hook.

Keys are for the living; to turn one against the outside is to stake your claim to everything within. The time will come when I will long to be unburdened, necklace to paperback, and when that day arrives I want someone orderly and calm on the block, someone honest, good-humored. Someone who earns his pay wiping my life as clean as he can so someone else can get her use of it. Believe I would, the auctioneer says. Believe I would.

Pacing the Siege Floor

Mark the smoke on the horizon and follow it down to the factory on the riverbank. May be winter outside but in here it’s always summer, sweat-drenched men moving slowly around the thrumming furnace, twirling rods whose ends burn with molten glass.

Say you spend your working life making objects of someone else’s choosing. You turn your attention not to the thing itself but to the process of making, losing yourself in repeated motion. By shift’s end, the lehr is lined with your work, dulling as it cools, the belt ticking it slowly toward the shipping floor.

You might sign your work; some do, neat script on the bottom of the candy dish, distinctive stamp attaching handle to basket. But this is the exception, not the rule. The closest I’ve found is the divot dimpling the bottom of the amber drinking glass, the mark where the blower broke the hollow rod free.

The World Is on Fire

The World Is on Fire