- Home

- Joni Tevis

The World Is on Fire Page 10

The World Is on Fire Read online

Page 10

Summer will swoon you but these winter roadsides hold a grudge, ash gray and brown, lichen splatter, shiny holly tree. From high up here you can see plenty, but not the indigo reservoir that cools the nuclear turbines nor the sunfish that swim in that warm bathwater, nipping the freckles on your thighs. Not the gashes in the red clay where someone ran off the road nor the junked cars arranged in curving ranks by the river that marks the county line. Not Easley High School, not the stadium nor the auditorium the Works Progress Administration built in ’39. Not the shadowy seats bolted to the floor, their green velvet crushed by generations of rumps in slacks and skirts, the fabric’s weave pressed into the nap—grosgrain, twill, dimity, denim, lace overlay. Fabric we once wove here.

We should go. The sheriff could drive up the road any minute, and the wind’s cold; your palms burn when you touch the rail. But before we leave, look over your shoulder and see one thing more: the town, my town, its white-painted churches gleaming in the valley and its tin water towers like old spoons. The towers fed the mills. IPA SOUTHERN, the painted letters say, ALICE MANUFACTURING, PLATT SACO LOWELL. Fragments of a dead language now but I stretch my mouth to speak them.

I wait at the red light in town and watch cars stream past. I don’t know any of these faces now, not those, not those, not yours. The sign outside the carpet outlet reads DISCOUNT HARDWOOD $2.99 SQUARE FOOT / REV. 6:1-17. That’s the part about the four horsemen of the apocalypse. Pale horse, pale rider.

If the fabric that separates earth and eternity is so threadbare, a chute to hell yawing open beneath your feet at any moment, then it makes sense to name your roads Gethsemane or Golgotha, Sinai or Calvary. Set aside even common land as hallowed. There is no bright line between now and forever. MAY YOU TAKE A LIKING TO THE GOOD LORD, that old sign on Highway 8 said, HE LOVES YOU. And the one beside 183, IT IS APPOINTED UNTO MAN ONCE TO DIE AND THEN THE JUDGMENT. YE MUST BE BORN AGAIN. If I painted a sign and planted it, what would it say? (What thou hast seen, write.)

Sometimes of a Sunday, I remember, a deacon would stand in the pulpit and give his testimony—the tale of where he came from, how he’d gone wrong, and how he’d found God. Even as a kid, I had heard enough of these to know what was coming, the genre conventions both a comfort and a bore. Still I had to respect the fact of his doing it, standing up in front of everyone. Not easy to know what to say. And I knew I would never have to. Back then it was only men who were called. Times have changed.

Say, the little children demand after asking a question. Say. Listen well and I will.

Warp and Weft

Tell me a story you know by heart.

All anybody could talk about that summer was the rain. Tomatoes split, pole beans molded, muskmelons turned to rot. Roadbeds gullied and the jockey lot washed out. Boughs exploded off oak trees. Mountainsides slid downslope in a crush of mud. The sign at the Baptist church said WHOEVER IS PRAYING FOR RAIN / PLEASE STOP.

And the song I couldn’t shake was “When the Levee Breaks.” Memphis Minnie Douglas and her husband, Kansas Joe, wrote it about the devastating 1927 flood that killed nearly three hundred people and wiped out tens of thousands of acres of the Mississippi delta. Refugees from inundated towns waited in tent cities above another, bigger levee while they figured out their next move. Thousands of them left the delta forever, setting off for cities like Chicago in what became known as the Great Migration.

The version of the song that most people know is Led Zeppelin’s, and the classic-rock stations around here play it plenty. John Bonham’s drum line—fleshy, thumping, heavy as a millstone—sounds like dread made physical, and yet somehow it’s tempting. It catches your ear and you sidle over, lean against it. Down on the river’s edge, weeds grow in the clay. Surely there’s no harm in letting your toes play in the water, in the bodied current, thick with silt.

Little tunnel, dark as a culvert. I crawled inside on hands and knees until I reached the middle of the smokestack and could stand, cool walls around me, circle of sky high above. Steel rungs mortared into the brick ran to the top; it would have been somebody’s job to climb the ladder, now and then, and check on things. I knew I shouldn’t be there.

It was a muggy July morning twenty-three years after the mill closed for good. Thickets of blackberry canes fortified the fence and scribbles of green creeper fluttered against the walls; the overall effect was that of a castle left to wrack and ruin while its inhabitants slept off a potent curse. I jumped the fence with my husband, David, and my friend Brad. I’ve known Brad since we were kids, a time when hundreds of people—our classmates’ parents—made their living here. But over time cheaper imports flooded the market and this mill went the way of most upstate factories. A scab-dark work glove, swollen with rubber warts, lay bloated in the weeds.

A hundred and fifty feet tall, made from clay very like the stuff beneath our feet, the stack was visible for miles, and like all of these old stacks it had little trees growing from its top.

Standing inside, I was at the center of something, and felt it. Behind me, the cleaning tunnel; in front, a dark mouth leading to the boiler. Something in me said Leave. It’s dangerous to treat with the past, and you can’t stay as long as you’d like. The place smelled deliciously of cool earth but there was no ash left in the pit, only brick powder, crushed-flat beer cans, and a dirty sign reading KEEP OUT.

Why do the mills pull me? I never worked in one, didn’t grow up on the mill hill. I moved here with my family when I was small, and left at eighteen for college in another state. I didn’t expect to move back; there weren’t jobs. Over the next dozen or so years, I lived and worked in six other states. When I finally landed, I ended up just down the road from where I’d started. It seemed there was something important to understand about that, about here.

Boosters used to call this part of South Carolina the Textile Capital of the World, and it wasn’t idle talk. You could sleep all night on our sheets and in the morning wash your face with our ring-spun cotton. Drink your coffee at a table spread with Dacron, slice sausage loose from local stockinette, press a shirt pieced here with an iron insulated by woven cotton electrical cording. These mills made twill and sateen, T-shirts and cardigans and lace and fiberfill. They made the diaphanous curtains with which Christo fenced the hills of northern California; they made space suits and parachutes for the Apollo astronauts. Braid, yarn, griege cloth, carpet. Webbing, florist wire, fiberglass. To keep a child’s idle hands from the devil’s business, you could buy a bag stuffed with the loops of many-colored stocking remnants. We had a handloom on which you stretched the loops over little teeth (warp) and a steel hook with which you could pull a second loop over and under (weft) and make a pot holder.

But by the time I started high school just down the hill, the mill had shut down and somehow I missed it. Brad and I were in the marching band together, and when we played our home games, our music would have bounced off these very walls. Yet in my memories of those Friday nights, where the mill ought to be there’s blank space.

If you could get a better perspective, say by climbing the rungs hidden inside the smokestack, here’s what you would see: the roof’s wide expanse, dimpled with stale rain; crackerbox houses in neat rows; the funeral home; the Hotel Easley (now condemned); the railroad tracks gleaming in the morning sun. If you stood at the top of that stack, high above the ground, leaves would brush your face from the little sumac trees that grow in the rim’s worn-down clay. Of the sumac, my field guide says, “a dear child has many names”: sumach, summaque, shumac, shoemake. The stack was once the life of the mill, breathing out black smoke. Cold now as a copperhead’s mouth. What does it mean to lose who you are?

In the fall, sumac blazes red and orange; you can use its wood to make picture frames, napkin rings, or darners, or you can boil its leaves to make black ink, with which you can write all this down to help you remember.

Listening to Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe singing, your ears play tricks on you. For a blues song “When the Lev

ee Breaks” is almost upbeat. But Memphis Minnie knew hardship. What hadn’t she seen? Playing Beale Street corners for dimes by day, entertaining hungry men for rent money by night. In her early teens she toured with a circus—ribby tiger, milky-eyed monkey, a steer whose horns she padded with rags. We all know sawdust but she knew chalk, splintered tent peg, a dancer pressing spangles in riverbank mud.

Did she see her childhood farmhouse lapped with waves? Did she see the river sixty miles wide and black with the topsoil of Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma? Did she see fence posts and sodden quilts float past; did she see a hair bonnet, drowned children? The levees broke in 145 places. Water filled cellar, kitchen, haymow; water thirty feet deep overtopped headstones, apple orchards, clotheslines, maple trees, chimneys. All the fenced and tended places wrecked.

A hundred years ago, many of the workers in these mills were the first in their families to leave the nearby mountains for town. Agents attracted them with rental houses owned by the factory. Simple places by today’s standards, but most eventually had electricity and running water, and little yards in back where folks kept patches of corn, peas, and greens to supplement what they bought at the company store. And many of their thrifty mountain ways they kept, not from sentiment but necessity. Make no mistake: the start of this was the end of something else.

But the accounts I’ve read speak of a sense of shared life that marked those years. People didn’t have much to spare, but none of their neighbors did either. The whistle regulated daily life, from the 8:00 a.m. start of first shift, to the 4:00 p.m. that marked the beginning of second, then third at midnight. Wednesday was prayer meeting and Sunday was preaching; the mill built the church and paid the preacher. If you had athletic talent, you played on the mill baseball or basketball teams. When people say they miss the mills, part of what they mean is they miss community. Easter-egg hunts, fishing contests, nicknames: Pokey, Mongoose, Ding Dong, Humpy. Jet Oil, Obb, Chili Bean, Gumlog. We wish we knew the stories behind the names; we want to belong to a story ourselves.

On Led Zeppelin IV, Page, Jones, Bonham, and Plant share Levee’s songwriting credit with Memphis Minnie. And Jimmy Page produced it in 1971, but for all the special effects in the song—playing the harmonica echo slightly before the actual melody, slowing down the replay for a “sludgy” effect, panning the instrumentals around Plant’s howl so everything swirls around him—the most powerful trick might also be the most simple. They set up Bonham’s drums at the bottom of a staircase. The drums sound prehistoric but the kit was fresh from the factory. It’s not just the heads (plastic) and the sticks (hickory) you hear, it’s the building, the tall, narrow space that you could, by some lights, think of as a tower.

The microphone is your ear, listening from high above to the roar and pound from below. Of “Levee,” Jimmy Page said, “It suck[s] you into the source.” Said John Bonham, “I yell out when I’m playing. I yell like a bear to give it a boost.” In the pauses between notes, the beat presses itself against your body like water. You can’t touch bottom but you know if you could, deadfall branches would snag your ankles. Said Bonham, “I like it to be like a thunderstorm.”

That rainy summer turned into a glorious fall, and because this is a small town, I discovered that the current mill owners—whose property I had, yes, trespassed upon—were good friends with my supervisor at work. Unaware of my sin, they invited me to tour the mill, which they planned to turn into apartments and had gotten listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The mill owner took a key from its hiding place and unlocked the front door. When we stepped over the threshold, the temperature dropped and we blinked in the sudden darkness; the windows were bricked up, the doors covered with plywood. The looms had been auctioned off long before, but when I played my flashlight across the floor I saw the square bolt heads that had anchored them. The boards underneath were lighter than the aisles, which had been darkened by the tread of countless feet. As the owner explained how the apartments would be arranged, I thought instead of how crowded it must have been, girls pushing carts down the narrow alleys and replacing full bobbins with empties, the machines’ thunder and clack. High above us were the pipes that had sprayed mist to keep the cotton mellow, and dead lightbulbs draped with old lint.

In the office, a giveaway calendar clung to the wall: a full year with no pages torn out, January 1990. I had almost expected to find that—but not the skein of plastic garland from the last Christmas party, nor the memo on the lunchroom floor detailing the exit-interview procedure: FOR THOSE EMPLOYEES WHOSE JOBS WILL END TODAY.

The newel post on the staircase was raised in the middle like a blister, its paint polished away by thousands of palms. We headed upstairs, where a training room held an old Draper loom. I shone my flashlight over it; the beam lit up a circle of threads, both filling and warp. It had been someone’s job to wind the thread in taut parallel lines around the teeth of the beam. “I loved drawing-in,” one skilled patternmaker said in an interview I read. “I enjoyed it more than anything I’ve done . . . honest to goodness, I’d rather draw in than eat when I was hungry,” she said. “The only thing I ever done in my life that I really loved.”

I’d seen an old photograph of a loom fixer seated in front of a frame like this. In his right hand he held a crescent wrench, and his left hand bore no wedding band, maybe because of the tight spaces in which he had to work. A ring could get caught in the machinery and then he’d lose the finger. She must have known he didn’t love her the less.

I imagine the lights flickering and the workers diving under the machines; when the power surges, the looms get out of whack, and the arm throws the heavy shuttle hard across the weave room. I see the man fix the loom and the weavers get back to work, cotton sheeting with a figured pattern of striped blue and red around the edge. The shuttles fly back and forth and the cloth grows and grows and when the roll is full the doffer razors it free, runs it downstairs to ship.

And the sheets stretch tight over beds sick or marital or childbirth. Cut in pieces they shroud okra and tomatoes from the garden and catch the pump water where the housewife shakes the vegetables dry; stitched in a line they make curtains and bloomers and pillowcases; quilted in layers they diaper infants; torn in strips they bandage the hurting. The banner on the truck that rolled down Main Street in the 1919 Armistice Parade read, WE MADE BANDAGE CLOTH FOR THE BOYS WHO BROKE THE HINDENBURG LINE. Rafters and floors of yellow pine, red brick walls, iron machines enameled green. Shuttles dark and quills pale poplar. Cotton so white after bleaching, and fat coils of roving going narrow as they seine through the needle’s eye. One worker said of the old days, “You sucked the thread into the eye of the shuttle with your mouth.” Workaday kiss.

We walked the floor together, moving slowly through the darkness like people floating in deep water. My flashlight picked up dim forms and shapes—broken pallets, a barrel of bobbins. Like the divers at the bottom of nearby Lake Jocassee who swim past the porch of the old summer lodge, two hundred feet down, or the cemetery, its gravestones pale teeth looming in the murk. When we turned to leave, we passed an open door scrawled with spray paint. TURN BACK, it said. YOU’RE NEXT.

The trouble with creating a song that depends so heavily on production is that it’s almost impossible to recreate live. After a few attempts in early tours, Zeppelin abandoned the effort. So the version of “Levee” I listen to must always be a relic, seven minutes and eight seconds snatched from the past.

I had a hard time getting a big picture of what the mills had been like. I scoured archives, read oral histories, left messages for folks who didn’t call back. It seemed like people wanted to forget what had been.

But one day I met a woman who’d worked in the mills her whole life—started out sweeping floors, moved up to the opening room, and had made it all the way to weaving instructor by the time the mill shut down. Third shift. Getting ready for her workday, she told me, she’d drape her tie threads around her neck like a scarf, for easy acc

ess when fixing broken warp. “You got your scissors,” she said. “All my blue jeans had a little hole where the scissors cut. Reed hook in your back pocket, rubber bands. No belt buckle, nothing to get hung up in the threads. . . . Masking-tape strips on your pant leg, to hold the thread until you tie it.” If you cut your fingertips, paint them with clear nail polish, lest the threads slice them clean open.

She’d spent her childhood on the mill hill in a haze of need, moving with her mother and siblings again and again just ahead of rent day. No tidy garden in the back—no time to tend it. One afternoon when she was four years old a man holding a badge promised her all the dimes she could imagine if she would just follow him a piece down the railroad tracks. Even that young she knew enough to run like hell, and got away.

We talked about what years of mill work would do to a body. Her back still troubled her, and her shoulders were out of joint from wrangling machinery. Growing up, she’d known healers, and it would be a help to find some now. “God gave people the gift,” she said. “Guess what? To take care of the people on the mill hill. But you had to believe or it wouldn’t work. They’d ask, do you believe?” Once, when she was burned, someone talked the fire out of her.

It’s been ten years since her mill closed. Of the noise and the pace, she said, “All I could ever do was dream of getting out. That to me was hell. And when you get home—you can’t go to sleep, you’re too exhausted.” But then again, she said, “I think it made people better. Respect, honesty. It bought the clothes. It built the houses.”

Before I left, she showed me a picture of herself with the rest of her crew. She’d posed with her coworkers on the mill’s front steps, as generations of workers had done before. Her group would be the last. She pointed out each person by name, punctuating the list with “you understand”—a habit of her speech. When I asked if she was sorry the mills closed, what she said surprised me. “Yes,” she said. “I wouldn’t hurt like I do now if I hadn’t stopped.”

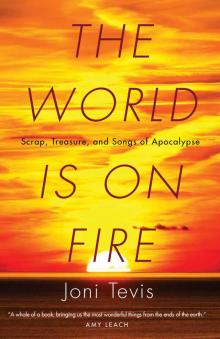

The World Is on Fire

The World Is on Fire